William Russell Birch, 1800, Penn Treaty Museum collection

The Fall of the Treaty Elm

On Thursday, March 8, 1810, Philadelphia’s Poulson’s American Daily Advertiser reported on a tremendous storm that blew through Philadelphia, uprooting the Treaty Elm:

“During the tremendous gale of Monday night last, the Great Elm Tree at Kensington, under which, it is said, William Penn, the Founder of Pennsylvania, ratified his first treaty with the Aborigines, was torn up by the roots. This celebrated tree, having stood the blast of more than a century since that memorable event, is at length prostrated to the dust! It had long been used as a land-mark, and handsomely terminated a north-east view of the city and liberties on the Delaware.” (Poulson’s American Daily Advertiser, March 8, 1810.)

This same news story ran in New York’s Columbian on March 10th, and Salem, Massachusetts’ Salem-Gazette on March 16th. A variant of the story ran in New York’s Evening Post:

“Philadelphia, March 7. After a blow from the north-east on Monday last, about 11 o’clock at night, the wind suddenly shifted to the west and blew a tremendous gale, accompanied with rain – the wind continued blowing violently the whole night and we fear has done very much damage thro’ the country. The chimney of Mr. Kay, hatter in Front-Street was blown down, the weight of which carried the whole of a one story kitchen into the cellar; a ship and brig at Kensington, were torn from their fasts and drove across the river and are ashore in Jersey. A great number of trees in and about the city were blown up by the roots, as was also the large tree at Kensington, under which William Penn, the founder of Pennsylvania, signed his first treaty with the Aborigines. This noted tree having stood the blasts of a hundred or more winters since that event, is at last tumble unto dust.” (The Evening Post, March 8, 1810.)

The Evening Post story was repeated in the New York Spectator on March 10, as well as the Boston Mirror on March 17. Another Boston paper, the Boston Gazette reported the story on March 19. Two weeks after the storm, the story spread across the country as the whole nation took interest.

On March 20, the story was picked up by the Connecticut Herald (CT), the Republican Star or Eastern Shore General Advertiser (MD), and the Washingtonian (VA), and the following day by two Connecticut papers, The Courier and the Connecticut Gazette. But the story wasn’t dead! On March 24 the Independent American in Washington, D.C, ran it, as did a Vermont newspaper, the Vermont Courier, March 28. By April the story had circulated as far north as Maine reports of the Treaty Tree being blown down are covered in the Eagle on April 3, and then again in Vermont’s Weekly Wanderer on April 6. Finally by April 28, when the story appeared in Rhode Island’s Columbian Phenix, it would appear that the whole country had read that the Treaty Tree was no more.

Before the loss of the Treaty Elm there was no need to create or erect a memorial to Penn’s Treaty since the tree itself was the memorial. However, without the famed Elm Tree the honored spot was in danger of disappearing forever. The riverfront of Kensington was booming and land was in demand. A story reported in Philadelphia’s Aurora and Franklin Gazette on April 12th, 1825 gives an idea of the activity:

“The District of Kensington at present exhibits a scene of animation in business seldom before witnessed. The hum of industry along its wharves and the building materials scattered profusely over all its streets, betoken a state of prosperous increase in wealth. Nearly 4,000 tons of shipping are on the stocks and it is intended shortly to commence two more large vessels. The street near the site of the “Treaty Tree” is to be straightened and an old building to be removed. The whole district in appearance and wealth is advancing rapidly.” [Freeman’s Journal]

Of course the Treaty Tree was no longer, but the spot where it once stood was becoming crowded with industry. The “old building” mentioned “to be removed” was the historic Fairman Mansion, the place where William Penn stayed upon his arrival in Philadelphia and which was later owned by Anthony Palmer, the founder of Kensington. The mansion house and surrounding property, including the Treaty Elm, was purchased by Matthew Vandusen (1759-1812) in 1795. He and his descendants lived there for 30 years before it was torn down to make way for “progress:” Beach Street was to be straightened and it is said that the Vandusens wanted to expand their shipyard. After the removal of the mansion house, several smaller homes were built on the site and members of the Vandusen family continued to live on the property.

It would appear that when the Treaty Tree fell on March 5th, 1810 that the tree was uprooted and, while it drew a crowd in the ensuing days, the tree was not immediately removed. It is reported that the original Penn Treaty tree on the Vandusen estate at Kensington became so valuable and so highly prized by relic hunters that the family found it necessary to have a guard placed about the premises to prevent its destruction. It was finally decided to pull the rest of the old tree down, and the trunk and branches were made into chairs and other artifacts, many of which became the property of the Oliver estate by hereditary right. Captain Paul Ambrose Oliver was the husband of Mary Vandusen, the daughter of Matthew Vandusen, the patriarch of the family.

The Founding of the Penn Society

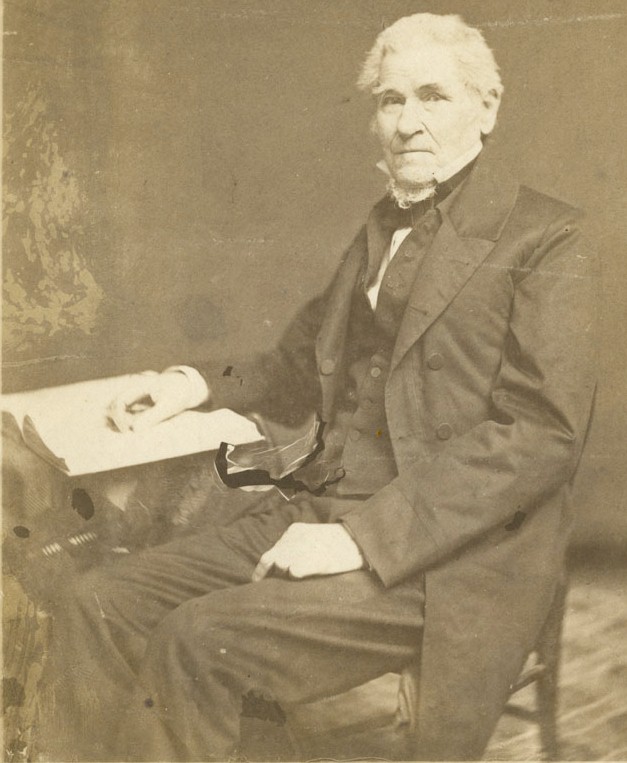

courtesy the National Portrait Gallery

Even though it was not until 1892 that the City of Philadelphia finally purchased the property to create Penn Treaty Park, it was actually much earlier when the first efforts began to save the history of that memorable place.

Roberts Vaux (1786-1836) was the first in a long line of Philadelphia’s citizens who came forward after the Treaty Tree was lost to begin the dialogue which would eventually lead to erecting a memorial to honor Penn’s Treaty with the Indians at Shackamaxon.

Roberts Vaux was a birth right Quaker from a prominent family who was sympathetic to the Indians’ cause during a time of difficult resettlement. His background of Quakerism and interest in the survival of the American Indians most likely led him to his interest in William Penn’s Treaty with the Indians. Vaux was very much an activist, being a vocal abolitionist, as well as taking a great interest in the penal reforms at Eastern State Penitentiary, and in the emerging Public School System of Philadelphia.

of Philadelphia

John Fanning Watson (1779-1860), an antiquarian and historian, well known in Philadelphia at that time for his collection of historical artifacts and manuscripts, as well as his vast knowledge of Philadelphia’s history, was also an early pioneer for the recognition of Penn’s Treaty. Watson and Vaux were on the same committee of History, Moral Science, and Literature at the American Philosophical Society. In an attempt to capitalize on the enormous enthusiasm at that time for General Lafayette’s memorable visit to Philadelphia in 1824, Vaux and Watson organized the Society for the Commemoration of the Landing of William Penn, better known today as the Penn Society.

Lafayette’s well-received visit to Philadelphia harkened the minds of the people back to the days almost fifty years previous to the American Revolution. Twenty-two of the original members of Vaux & Watson’s Penn Society were subscribers to a portrait that was commissioned of Lafayette. The renewed historical interest generated by Lafayette’s visit was an important moment in the awakening of the “proper” Philadelphians’ minds to her historic past and the forming of the Penn Society, an event that saved the memory of Penn’s Treaty.

Membership to the Penn Society was open to “any person of good moral character” who was approved by the board. The dues at that time were ten dollars for a life membership. Early members and founders of the Penn Society, such as Roberts Vaux, John F. Watson, Peter S. du Ponceau, J. Francis Fisher, J. Parker Norris, as well as others, were in a sense also the “founding body” of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, an organization that was formed at this time.

The purpose of the Society was “to portray the character, and perpetuate just and grateful recollections of the services of the illustrious lawgiver (William Penn) and his companions.” This generous purpose, it was believed, could be carried into effect, by the annual delivery of discourses – “by preserving representations of scenes of great interest; and also by constructing monuments at various points, distinguished by events that shed luster over our early annals.”

The Penn Society’s inaugural meeting, on November 4, 1824, was a sumptuous banquet held at the house in Letitia Court that was once the home of William Penn himself. The Society’s purpose that night was to commemorate “Penn’s landing on the American shore” in 1682, and to honor “the memory of his virtue.” The Penn Society dinner became an annual event and in 1825, Charles Jared Ingersoll delivered an address to a group that included President John Quincy Adams. Adams received a complimentary relic box made from the Treaty Tree and it is said that much to the dismay of the Society, Adams used the relic as a snuffbox.

Penn Society Supports a Treaty Tree Memorial

One of the objectives of the Penn Society was to use the membership dues to erect monuments to the “fame and memory of their great founder.” Roberts Vaux in a paper titled A Memoir on the Locality of the Great Treaty Between William Penn and the Indian Natives, in 1682, and read before the Historical Society of Pennsylvania on September 19, 1825, called on the Historical Society “that measures be put in train for erecting a plain and substantial Obelisk of Granite, near where the tree formerly stood at Kensington, with appropriate inscriptions.”

As one newspaper reported years later on the founding of the Penn Society and the erection of the Treaty Memorial:

“Away back in 1824 some of our grave and revered citizens, who were beginning to cultivate historic tastes, assembled in a spirit of reverence for the past, ate their dinners and made their speeches and became enthusiastic over the sacred memories that hovered around their place of meeting, Penn’s old cottage in Letitia Court. Here they created the Penn Society, and seventeen years after the Treaty Elm was blown down in 1810 they erected in order to preserve knowledge of where the great elm stood, for future generations, the little monument on or about the same spot. This monument, it is said, was the first erected in Philadelphia, and for this reason, if nothing else, it is fortunate that it has been preserved. There are those who claim that it commemorates only a tradition, but nevertheless, poets, patriots, philosophers and historians have accepted the story of Penn’s Treaty of friendship and peace with the Indians under the great elm at Kensington.”

Thus the Penn Society erected its memorial to Penn’s Treaty, an obelisk standing slightly over 5 feet with inscriptions inscribed on all four sides reading (by the compass,

north, south, east, and west):

Treaty ground of William Penn, and the Indian Nations, 1682, Unbroken faith.

William Penn, Born 1644, Died 1713.

Pennsylvania, Founded, 1681, by Deeds of Peace.

Placed by the Penn Society, A.D. 1827, to mark the site of the Great Elm Tree.

In a more contemporary description of the event, the Pennsylvania Gazette of November 24, 1827, reported the following:

“[Penn’s Treaty] was held at Shackamaxon, (now Kensington) as Mr. Roberts Vaux has satisfactorily shown in his memoir in the Historical transactions. That situation was selected, because it was a favorite resort of the natives, where some of the first emigrants, members of the Society of Friends, originally bound for West New Jersey, had taken up their bode, more than a year antecedently to the arrival of Penn in the Delaware.

[The Elm Tree], the stately and ancient land mark, so long an object of respect, was prostrated during a storm in 1810, and soon after that even, many other changes occurred in that vicinity, contributing to obliterate the remembrance of the place where, and perhaps also, in some measure, to obscure the principles upon which that Treaty was made. To rescue the locality from oblivion, and to preserve in honorable recollection, the righteous deeds performed upon it, so far as these ends might be within their power, was a duty, which the Directors of the Penn Society were anxious to fulfill. A Committee was accordingly appointed, consisting of Roberts Vaux, Joseph Parker Norris, and John Bacon, Esquires, with authority to cause a suitable memorial to be placed there, if the proprietor of the soil would grant permission. The consent of the heirs of the late Mr. Matthew Vandusen being obtained, a marble monument has been erected on the spot….The position of this monument is on the bank of the Delaware, at Kensington, near the intersection of Hanover and Beach Streets.”

It is said that the famed architect John Haviland created the original obelisk that was designed for the Penn Society, but it proved too costly for the newly formed Society to erect and thus a simpler model was substituted for it. The monument was placed on the grounds of the Penn Treaty Wharf, at the spot where the Treaty Tree stood. Presumably the men placing the monument would have known exactly where the tree stood as they were all living when the tree blew down 17 years previously. This obelisk was the first public monument erected in the city of Philadelphia, although at the time of its placement it was actually the District of Kensington, not the City of Philadelphia. Kensington did not become a part of the city until Philadelphia County was consolidated into the city in 1854.

Penn Society Reported on Nation Wide

The formation of the Penn Society created quite a stir and was of nationwide interest, as this sort of society was one of the first of its kind. It consisted of many of Philadelphia’s elites, and its annual dinner attracted many notable people. Newspapers from as far away as Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Indiana, and Washington, D.C., reported on the activities of the Penn Society and as a result the nation became more aware of Penn’s Treaty with the Indians.

The New Hampshire Statesman and Concord Register reported on the Penn Society activities on November 5, 1825, after President Adams attended the annual dinner of the Society. A New Orleans’ newspaper, the Louisiana Advertiser, on November 27, 1826, reported on the Penn Society meeting, the address by Thomas J. Wharton, and the dinner afterwards at the Masonic Hall. The Raleigh Register, and North-Carolina Gazettepublished reports of this same meeting earlier on November 10.

Several Washington, DC newspapers are found reporting on the Penn Society as witnessed by stories in the Daily National Journal of October 30, 1826 and October 29, 1827, as well as when the Daily National Intelligencer on November 29, 1826 noted that:

“The Directors of Penn Society of Philadelphia has appointed a Committee to inquire into the practicability of placing a Memorial to designate the spot upon which the Elm Tree stood at Kensington.”

The Indianapolis newspaper, Indian Journal, reported on November 27th, 1828, about the Penn Society’s annual meeting for that year (the annual meeting is held on the anniversary of the landing of William Penn, October, 24, 1682). In the news story, the paper shows the historical respect and humanitarian nature of the Penn Society as it lists the various toasts in order, that were made at the dinner:

1. The Anniversary of the Landing of William Penn

2. William Penn

3. The Pilgrim Fathers of Pennsylvania

4. The Treaty under the Elm – “a text book for diplomats, whether monarchical or republican.”

5. Old Upland, the seat of the first Pennsylvania government

6. The Great Law

7. The First Tariff, which taxes the importation of Negro Slaves, Rum, and other Spirits

8. The Fragments of the Lenni Lenape, once the powerful sovereigns of Pennsylvania, may no cruel or avaricious hand disturb them in their last retreat.

9. Universal Education

10. The Three Lower Counties

11. Auld Lang Syne – the day of Old Philadelphia

12. Pennsylvania from the Delaware to Lake Erie

13. The Memory of the late venerable Judge Peters Volunteer toast by a guest: “Our ancient and faithful allies the Delaware Indians, wherever they may be carried by the destiny of nations, in Illinois, or Arkansas, we ask humanity to themselves and justice to their history.”

Notable in the newspaper account, the Penn Society makes two toasts to the American Indians, as well a toast to Penn’s Treaty with the Indians, all delivered with respect and honor.

The Beginning of the First Decline

When the Penn Treaty Memorial was erected it was looked upon as a “temporary affair” as the Penn Society proposed to establish a much larger monument at a later date, but they were never able to do this, and the little monument remained.

The two decades (1827-1847) following the original erection of the Penn Treaty Memorial in 1827 saw a decline in the upkeep and care of the monument, as many of the original founders of the Penn Society died and interest waned. Roberts Vaux, the real impetus for the erection of the monument died in 1836, followed by the Penn Treaty researcher Peter S. du Ponceau at the age of 88 in 1844. John Fanning Watson lived until 1860, however, the Penn Treaty Memorial was more Vaux’s idea: Watson was getting on in age and lived out in Germantown, a considerable distance from the Memorial.

The task of caring for the obelisk seems to have passed from the downtown elites who first erected the memorial into the hands of the local Kensingtonians who lived near the Monument.

One newspaper reporter, writing in the local North American and Daily Advertiser, on January 28, 1845, states that:

“The monument in Kensington on the site of the old elm tree, in commemoration of the celebrated Penn Treaty, ought at present to attract attention. It seems that very little regard is paid to it generally, the care for some time past taken having been bestowed by several citizens of the neighborhood, and perhaps one or two others who have felt an interest in the preservation of the memento and its appearances.

We learn that at the present time the fencing around it is in a dilapidated condition, and that a part of it has been thrown down. – Something should be done by our authorities or public institutions [to] secure the ground upon which the monument is erected, and to preserve the whole from injury.”

The very next year (December 29,1846) workmen employed to excavate the site of the Treaty grounds in Kensington dug up a large number of roots of the old Elm Tree. This circumstance caused “much of a stir among the denizens of the District and others, all of whom were anxious to carry off some portion of the precious relic, to keep as a remembrance of a scene celebrated in the history of the founding and settlement of Pennsylvania.”

One problem, however, that arose and is noted in the Journal of the County Board of 1848, is that “‘The Penn Society did not, neither as buyer nor renter, secure a right to the occupancy of one foot of the soil covered by the “monument,” hence the monument remains where it is upon mere sufferance and may be moved and the space cleared whenever the order to do so shall be given.”

In this 1848 report, the County Board, recommends “in strong language” the acquisition of this property, stating, “The failure to act would cause unceasing regret for an irreparable loss.” The fact that members of the County Board argued so strongly in 1848 to purchase the property on which the Penn Treaty Monument was erected, in order to save it from oblivion, is rather startling when one thinks that the City did not actually acquire the property until over 40 years later. To get a better understanding of the thoughts on the County Board in 1848, we reprint here the reporting on that County Board meeting:

“The County Board met yesterday morning. Mr. Fernon, from the Committee on Estimates, to which was referred the subject of the purchase of Penn’s Treaty Ground, submitted the following report:

The Committee cheerfully united in recommending the purchase of the site of William Penn’s Treaty with the Indians, held under the Elm Tree, at Shackamaxon, in the year 1682. This spot, whereon the founder of the State ratified a bond of amity and peace with the Indian natives, and confirmed that just and equitable code which distinguished the primitive days of Pennsylvania, should be protected from the pursuits of gain; and embellished with the emblems of patriotic sentiment and unbroken faith. Abounding in cherished associations and legends hallowed by time, it commemorates an event embalmed in history and renowned over the world.

As an example of wise policy and profound regard for the rights and opinions of mankind, succeeded by great beneficial results, William Penn’s conference with the American Aborigines has no parallel in the annals of contemporary States, or among nations in other times. It is the bountiful legacy of Pennsylvania – the gift of her sage who extended the arts of civilization and the blessings of mild laws far into the wilderness – who fostered friendship and concord with the Sachems and warriors of the Indian tribes that roamed the forest and owned the hunting grounds.

The love of country, the dictates of Pennsylvania feeling, and especially the local relation of Philadelphia to the incidents of that period and the events of Penn’s life, all inspire veneration for the Treaty, and demand the preservation of its site from irreverent use.

The custom, which, to indulge a hankering for new appearances, modernizes the antique homestead and venerable public edifice, and destroys interesting mementoes of centuries and generations gone by, thus year after year diminishing the number of olden relics, consecrated to the good deeds and virtues of the past, and identified with the early settlement and moral grandeur of the Commonwealth, should be checked; or, at least, it should not be permitted to invade the birth-place of Penn’s fame, nor mar the sacredness of memories which hallow the spot of earth where the branches of the Elm tree spread over the “Council” and furnished shade by the river’s side.

The present condition of the Treaty Ground is amply suggestive of regretful comment. The monument, which is a plain marble shaft upon a double square base, measuring from the foundation to the summit, five feet nine inches, does not, as the inscription upon it asserts, mark the site of the Great Elm Tree. The actual site of the Treaty Tree, which was blown down on the third day of March, 1810, is marked by a post put into the ground at the time of the disaster, and which still occupies its original position at a distance of about fifty-one feet, in a line south southeast from the monument erected by the Penn Society in the year 1827, and placed where it is now to be seen by permission of the owners of the ground. The Penn Society did not, either as buyer or renter, secure a right to the occupancy of one foot of the soil covered by the monument and embraced within the dilapidated paling which once surrounded it, hence the monument remains where it is, upon mere sufferance, and may be moved and the space cleared, whenever the order to do so shall be given.

The Treaty lot being private property, of course it may at any time be built upon, or disposed of in such manner as may forever bury it from view and bar the public from its possession. If this misfortune were to happen, it can readily be imagined how sincere would be the sorrow and universal the regret for its irreparable loss; and it may happen, if measures are not now adopted to avert it, inasmuch as the late proprietor divided the estate into several portions, among his heirs, either of whom may at any time dispose of a separate interest.

Therefore, to guard against this emergency and to secure for a appropriate public use, the scene of an imperishable event, it is deemed expedient and proper that the Treaty ground should be purchased by the county, in order that the citizens of Philadelphia city, districts and townships, may share the honor of contributing to an object prompted by gratitude and sanctioned by the highest considerations of utility and duty.

The Committee offers the following resolution, and unanimously recommends its passage:

Resolved, That any money in the Treasury, not otherwise appropriated, not exceeding the sum of four thousand five hundred dollars, is hereby appropriated for the purchase, for public use, of the lot or piece of ground known as the site of William Penn’s Treaty with the Indian Nations, held under the Elm Tree at Shackamaxon, now named Kensington, in the year 1682; and the County Commissioners are hereby authorized and requested to make said purchase from the owner or owners of said lot or piece of ground for the purpose aforesaid.

Upon the question of adopting the resolution there was a debate, in which Messrs. Matthias and Forsyth opposed the motion, and Messrs. Fernon, Finletter and Roberts advocated it.

Mr. Matthias moved to postpone the whole subject for the present, which was not agreed to by vote of five yeas, to eleven nays. And on the question the yeas and nays were required, and were as follows:

Yeas – Messrs. Crabb, Daly, Downs, Fernon, Finletter, Laughlin, Lowine, Roberts, Steel, and Benner. -10

Nays – Messrs. Forsyth, Matthias, Diehl, Hart, Smith, and Vansant. -6

So the resolution was agreed to.”

(North American and United States Gazette, (Philadelphia, PA) Wednesday, December 27, 1848; Issue 16,504; col H)

The County saw the danger of the Penn Society’s monument subject to legal removal by anyone who presently owned the land or by any future landowner. Apparently at the time the Penn Society erected their monument they had an understanding with the Vandusen family at that time, but later generations of the family do not appear to have taken an interest in the preservation of the memorial.

The County Board consequently adopted the resolution at this time and a sum of money was appropriated to purchase the property. After the matter had gone thus far, the County Commissioners assumed that they had no right to purchase or sell real estate. An appeal went to the Legislature to pass an act empowering them to make the purchase. Nothing happened and the money was absorbed in the expenditures of the succeeding fiscal year. Another great opportunity for the government to purchase the land and create a park was lost.

A Boston newspaper (The Boston Daily Atlas) picked up on the story of trying to save the Penn Treaty Monument site. On January 1, 1849, while discussing the hoped-for $4500 appropriation by the Philadelphia County Commissioners, the reporter mentions that:

“The [Penn Treaty] ground is now covered by huge piles of boards from an adjacent saw mill, but for this timely appropriation it would inevitably have been built over. Within a few years back this portion of the suburb of Kensington has become crowded with factories, mills, and ship-yards, and even the Monument has not more than a dozen square feet of ground appropriated to it.”

However the appropriations project lay in abeyance until 1852, when it was revived and a survey made, upon a petition by the Board of Commissioners of the District of Kensington to the Quarter Sessions Court. A jury was appointed to assess damages. H.G. Jones, Jr., from the Elm Tree Treaty Committee of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania reported at a meeting of that Society on December 24, 1852, that the jury had assessed damages and that the matter was now still in the Court of Quarter Sessions. The Historical Society previously approved the action of the Legislature and expressed a hope that the Commissioners might be induced to take early action, but the entirematter came to a halt and would not be revived again until the City of Philadelphia purchased the property in 1892.

“So far as the expression of public opinion has been enlisted the indications are strongly in favor for the purchase of this ground. The record of Penn’s treaty or conference is a singular feature in the early history of Pennsylvania, unparalleled in the annals of any other Commonwealth, and the spot where the simple touching drama was performed by the Quaker and the Indians should long ago have been made one of the chief attractions of Philadelphia. The spectator, whether a tourist from abroad or a citizen belonging in our midst, is in either case shocked and mortified at the spectacle presented in its dilapidated condition, and turns away mourning the indifference which permits it so to remain.”

By 1856 the “For Rent” signs started to appear at the Penn Treaty site. Washington Vandusen, the presumed owner at this time, put an advertisement in the Philadelphia newspaper, the North American and United States Gazette:

“Penn Treaty Wharf to Let – The whole part of the above Wharf to be let. River front of 180 feet. Apply to W. Vandusen, Hanover, 2d door above Beach St., Kensington”

The advertisement ran for several days adding that the depth of the lot was 333 feet.

In February 1869, Mr. Adaire, presumably Alexander Adaire, a local Kensington lumberman, who served in the Pennsylvania State House, introduced a joint resolution in the House to appropriate $5000 to repair the Penn Treaty Monument. The resolution was not acted upon until the following month when on March 27 it was reported that the issue of “repairing the Penn Treaty Monument in the 18th Ward came up” and a Mr. Hickman moved to amend the resolution by reducing the appropriation to $2500, providing the citizens of Philadelphia subscribe a like amount. Forty-seven legislators agreed, thirty dissented and the measure passed. Locally, Philadelphia legislators Mr. Adaire, Dally, Holgate, Hong, Kleckner, McGinnis, Mullen, Michael, Stokes, Thorn, Whetham and Speaker Davis voted yea, with Mr. Bull voting no.

In September 1870, yet another resolution was introduced, this time in the Common Councils of Philadelphia. A Mr. Logan offered a resolution to appoint a joint committee of three from each Chamber (Common & Select Councils) to purchase the Penn Treaty ground. The resolution was referred to committee. The Finance Committee reported on the resolution and it was promptly postponed.

In April 1872, Washington Vandusen began again to place advertisements in the local papers about the Penn Treaty Wharf, however, this time he was offering for sale equipment from his lumber and saw mill business:

“For Sale, to be Removed. Penn Treaty Marine Railway. Cylinder Boiler, 30 feet by 30 inches; Circular Saws, Jig Saws, Belting, &c. W. Vandusen, Penn Treaty Wharf, 1309 Beach Street, Kensington”

This advertisement ran during the month of April 1872 as well as in September of 1872. His September advertisement shows him to be selling the Marine Railway and renting the wharf:

“Penn Treaty Wharf to Let and a Marine Railway for sale, with steam or horse power, jig and circular saws and fixtures. Apply to W. Vandusen, 324 Madison ave., Phila..”

By November 20, 1872, he no longer advertised the Marine Railway, but was looking to rent or sell the Penn Treaty Wharf. Presumably Vandusen, who was about 67 years old in 1872, was retiring, selling the business, and looking to dispose of the property as well.

More time went by and in a session of City Council, held December 16, 1880, local councilman Benjamin M. Faunce, of the Eighteenth Ward, introduced a resolution instructing the Commissioner of Markets and City Property to “employ a portion of the coping and railing” that they were removing from around Washington Square, “to fence in the Penn Treaty Monument.” Faunce’s resolution was referred to the Finance Committee.

Faunce, came from an 18th century Kensington family whose members made up the largest family of fishermen on the Delaware River and played an important part in the development of the area. He was probably concerned about protecting the Penn Treaty Memorial because for years the great majority of people forgot the existence of this monument. It was “friendless and alone, frequently buried beneath piles of lumber, its face hidden from the sun and the eyes of man.” Many times there were threats to remove it by the owners of the property on which it stood, but for some reason or other it remained.

An indication that the Penn Treaty Wharf might have become a hazard is recorded on July 1, 1886, when it was reported that John Dietz, a 65 year-old man of 1225 Leopard Street, had his leg fractured when one of the lumber piles that surrounded the Penn Treaty Monument fell on him. He was taken to the Episcopal Hospital.

However, the real sign of trouble at the famed Penn Treaty site was on March 4, 1890 when there appeared a “For Sale” notice in the Philadelphia Inquirer. This advertisement may have been the catalyst that began the final rally cry of Philadelphia’s citizenry for the founding of Penn Treaty Park, a cry that had been voiced for about eighty years, from the time the famous Elm Tree had fallen:

“For Sale. Penn Treaty Wharf. This very valuable wharf and historic piece of ground is situated on the S.E. side of Beach St., beginning 60 ft. 5 _ inches N. E. from Hanover and extending from Beach Street to the River Delaware; 85 feet 4 inches front on Beach street and 130 feet on Warden’s Outside Line. This property has an average front or width of 107 feet, the width or front on the warden’s outside line being about 130 feet and the width on the warden’s inside line for head of docks being about 107 feet. The distance from Beach street to the warden’s outside line is about 623 feet. See plan.

There is a Two-story Brick stable on the wharf. There is also a monument, with …four inscriptions on its four sides…. Sale by order of Heirs – Estate of W. Van Dusen, dec’d. For further particulars apply to John Van Dusen, Sen, 2124 N. Twentieth St., Phila…Sale on Tuesday, March 11, 1890, at 12 o’clock noon, at the Philadelphia Exchange, corner Third and Walnut Sts., By M. Thomas & Sons, auctioneers, 136 S. Fourth St.

The Penn Treaty Grounds were offered for sale by the Van dusen family and there was no legal remedy to prevent anyone from buying the property, removing the monument and clearing and building on the site. The idea that all remnants of Penn’s Treaty with the Indians could disappear from this spot forever became a focal point for those Philadelphians who have long desired a memorial park for Penn’s Treaty at this location.

A New Call for a Penn Treaty Park

At this same time there was talk in Philadelphia’s City Council about what to do with Kensington’s old West Street Burial Ground at Vienna (Berks) & Belgrade Streets. It had become dilapidated and a community eyesore. A number of families of the deceased had already removed a number of bodies from the old cemetery and had not refilled the grave sites. The focus of City Council’s talk began to be centered on turning this old cemetery into a public park for the residents of the area. However, on December 16, 1891, Kensington lawyer Joseph L. Tull appeared before the City Council’s Law Committee and argued against the taking of the plot of ground at Vienna and Belgrade Streets for a public park. Tull wanted any new square to be located at the site of the Penn Treaty Monument.

Joseph L. Tull’s family had been in Philadelphia since the time of William Penn, having moved to Kensington in the early 19th century from the Northern Liberties area. His father, John P. Tull, had a pattern making business on the Delaware River and was partners with the Landells, the family that ran the Kensington National Bank. The Tull’s first lived on Allen Street, near Shackamaxon, then on Shackamaxon, and had their business where the old sugarhouse was located, at Shackamaxon and Delaware. John P. Tull’s mother was a member of the old Germantown Pastorius

family.

Tull’s argument must have been persuasive, as the following month it was reported in the Philadelphia Inquirer of January 25 1892 that Philadelphia City Council and the Fairmount Park Art Commission were thinking about “joining hands” to work together for the establishment of a park to commemorate William Penn’s Treaty with the Indians.

The notion of some sort of mutual cooperation on the formulation of a Penn Treaty Park had been mentioned previously at the most recent annual meeting of the Fairmount Park Art Commission and was met at that time with approval by the group. Philadelphia artist John Sartain, who presided at the annual meeting of the Art Association, was a backer of the Penn Treaty Park idea, a combination of a public space and a site that would commemorate the historic event of Penn’s Treaty. Sartain thought “it was a grand thing to do” and accordingly he laid the idea before the art committee of the association at their next meeting and it met with approval.

On the City Council side, Thomas Meehan of Germantown’s 22nd Ward was reported to have made it his “life’s work” of establishing new public squares on the city plans, “for greater beauty and for more air and recreation for the masses of working people in their very homes.” Meehan was a world-renowned vegetable biologist, an original Fellow of the Academy of Natural Sciences, and a member of all the leading scientific organizations in his native England and his adopted America, as well as Germany, France, and Australia. He was also a one-time superintendent of Bartram’s Gardens and had his own nursery business in Germantown. He was a Republican councilman from the 22nd Ward for 16 consecutive years, until his death in 1901. His involvement in politics seemed to be a way for him to implement his ideas of greening Philadelphia.

Meehan was “delighted” with the Art Association’s idea of a memorial park since it fit into his plans for promoting open spaces. As it happened, his council’s committee had spent the previous day at the Penn Treaty grounds and was unanimously in favor of opening a new plot there. Meehan’s committee consisted of himself, Charles Roberts, Thomas Wagner, Nathan Lewis, and George W. Kendrick.

With the support from the Art Association to commemorate the place with a “memorial group” the idea sprung to life and was empowered by the dual quantity of prestige from the government and the elites of Philadelphia’s art community. This combination of the open space ideas of Council’s Meehan and the support of the folks at the Fairmount Park Art Association, was the alliance that was needed to finally get city approval and financial support for Penn Treaty Park.

On January 30, 1892, the City Council’s Committee on New Public Squares, the Fairmount Park Art Association, and the City Parks Association, were all recorded as being unanimously in favor of the “new square covering the Penn Treaty grounds.” The coming on board of The City Parks Association in the creation of Penn Treaty Park was another coupe for the park movement. The following letter by that group is a witness to their support of the park:

“Dear Sir: – It is an admirable suggestion to create a small park covering the site where the Penn Treaty with the Indians was made. Your suggestion seems to me a happy union of beauty and utility, since it aims to secure an additional space for fresh air and green trees, which will be greatly to the advantage of those who are unable to seek, beyond city limits, these necessities of our hot summers, and that it will also call attention perennially to an instance of just dealing with the Indians that is succinctly rare in our history. I do not know what practical obstacles stand in the way of carrying the plan into execution, but if any such exist I trust they may be speedily removed. I shall take pleasure in calling the attention of the City Parks Association to this project, and I have no doubt the association will gladly assist in furthering it.

January 25, 1892, Herbert Welsh”

Gaining Herbert Welsh’s support for the establishment of Penn Treaty Park was a positive development for the park enthusiasts. Besides being from the “Proper Philadelphia” class, Welsh was also one of the founders of the Indian Rights Association (IRA), which based its headquarters in Philadelphia. The IRA was a humanitarian group dedicated to influencing federal U.S. Indian policy and protecting the rights of the Indians of the United States, while promoting a policy of assimilation. The IRA was the most influential American Indian reform group of its time. The backing of this American Indian rights group helped solidify the general support for the creation of the park.

Herbert Welsh, like Roberts Vaux in earlier days, had a special affinity and respect for the American Indians, which connected both the men to the idea of a memorial park for William Penn and his Treaty of Amity with the Indians.

Acquiring the Land for the Park

The Penn Treaty grounds in 1892 did not present a significant site. The local newspapers reported the area as:

“…a wharf property, which is the scene of dirt, old carts, stray chickens, broken-down fences, a shanty or two, a small brick building, and most conspicuous of all, a sign reading: For Rent or sale, Apply John K. Van Dusen.”

The newspaper story goes on to say that the little treaty monument, “five feet high or less,” stands on the property in a corner nearest to Neafie & Levy’s shipyard. It was “erected by the Penn Society in 1827, and probably represented a bigger financial undertaking than a $200,000 park and $100,000 bronze group would be now.” The reporter states “the little statue has been so often moved about over the plot that the site of the great elm tree has been lost, so that the center would as accurately memorialize the treaty as it is possible to do.”

In order to build a park at this spot three wharf properties would have to be bought – Vandusen’s, Harry Bumm’s and Henry Plotz’s. Plotz’s wharf was next to Bumm’s and was the width of Hanover Street down to the river. The entirety of the three properties was less a little less than the usual size of a public square.

The aesthetics of the area were apparently not very pleasing to the reporter, as he goes on to state, “the only disadvantages presented from the artistic point of view are the attractiveness of the neighborhood, the Beach street railroad tracks and tumble down buildings in the neighborhood beyond.” He ends his piece by saying that “the fitness of a memorial group on the scene of the event, and advantages of carrying the great lesson of history ennobled by art into the hearts and homes of toiling masses of Kensington, may prove to be overwhelming advantages.” While a little repugnant in tone, his point is clear: a park commemorating the history of William Penn’s Treaty with the Indians would be great for the neighborhood.

The following month, on February 25, it was reported that “Bills were submitted to the Committee on Municipal Government” for Penn Treaty Park. Not only was Penn Treaty Park being founded at this time, but a number of other parks were proposed as well:

Walmouth Park (Kensington & Frankford), Stephen E. Fotteral Square (11th & Cumberland), Forepaugh Park (Broad & Dauphin), Vernon Park in Germantown, and another square at 3rd & Moyamensing.

On March 2, 1892 it was reported that Philadelphia’s City Council passed an ordinance to place Penn Treaty Park on to the city plan. Womrath Park and the Stephen E. Fotterall Park were the only other parks from the above-mentioned list that also were placed on the city plan at this time.

The very next day, ordinances were introduced into City Council and referred to committees, to appropriate $83,000 for the purchase of a plot of ground for park purposes, bounded by Beach and Hanover (Columbia) Streets, the Gorgas Estate, and the Delaware River, to be known as the “Penn Treaty Park.” Finally, on March 10 an ordinance was passed by City Council and signed by Mayor Edwin Sydney Stuart and with that ordinance Penn Treaty Park was officially placed on the “city plan.” Edwin Stuart would later go on to become the governor of Pennsylvania.

The dimensions of the new Penn Treaty Park were published in the Philadelphia Inquirer March 18, 1892. They were given as follows:

“Beginning at the east corner of Hanover (Columbia) and Beach Streets, thence extending along the southeast side of Beach street northeastward one hundred and forty-five feet nine and three-quarter inches, to a point on the line of land now or late of Edward W. Gorgas, thence along the same south twenty-eight degrees ten minutes fifty-five seconds, east six hundred and seventeen feet eight and one-quarter inches, more or less, to the Port Wardens’ line in the river Delaware, thence along the same southwestward two hundred and sixty-six feet six inches, more or less, to the northeast line of Hanover street produced and thence along the same northwestward six hundred and eighteen feet more or less to the southeast side of Beach street, the place of beginning to be called Penn Treaty Park.”

By summer 1892 the plans for Penn Treaty Park were drawn up and a hearing for the park’s development was to be held on July 18, 1892 by the Bosrd of Surveyors. In the Philadelphia Inquirer of July 15, 1892, there was a notice published stating that the citizens of Philadelphia were able to view the plans for Penn Treaty Park at the office of city surveyor Joseph Mercer. Mercer, a city surveyor for the 6th District, kept his real estate office and home at 1845 Frankford Avenue for a time before moving to the 1900 block of North Broad Street.

On April 22, 1892, the Council’s Finance Committee reported favorably on the ordinance condemning three acres of ground surrounding the Penn Treaty monument in Kensington for the purposes of creating a park. The price paid for the properties was not to exceed $85,000.

The Business of Building the Park

In January 1893 the Bureau of City Property budgeted $15,000 for improvements to Penn Treaty Park, which included “grading, sodding, paving, fencing, coping , and otherwise improving the park.”

On March 2, 1893, Kensington State Representative William Stewart introduced a bill in Harrisburg to appropriate $5,000 for the erection of a pedestal for the proposed Penn monument to be erected at the new Penn Treaty Park. However, on May 18, 1893 it was reported that the Pennsylvania State House’s Appropriation’s Committee reacted negatively to appropriating any funds for the pedestal.

On April 12, the City of Philadelphia began advertising for bids for “repairing wharf and bulkhead at Penn Treaty Park, foot of Hanover Street.” On May 30, the city was advertising for bids for “improving Penn Treaty Park” Any bids were to be sent to Abraham M. Beiter, Director of the Department of Public Safety, Bureau of City Property. The bids would be accepted until June 5, 1893. The city received one bid that exceeded the appropriated amount for the park by $2,646.

One aspect of the park improvements involved the re-planning of the Penn Society’s Penn Treaty Monument and re-cutting the eroded inscriptions engraved on it Local toughs had taken to using the monument as target practice for throwing rocks.

On May 7, 1893, it was reported that Chief Eisenhower, of the Bureau of City Property, had before him, plans for Penn Treaty Park that would make it “a gem among the city’s pleasure grounds.” The entire wharf property was to be turned into a public square and a handsome pavilion was to be erected at the end of the pier. The small building on the corner of Beach Street was to remain and the area, in memory of the tree under which Penn made his famous treaty with the Indians, was to be planted exclusively with elms.

Chief Eisenhower was again in the news on July 4, 1893 when he gave a magnificent flag to Penn Treaty Park. While not officially dedicated and open, the park had already started to attract crowds. Those gathered on this Fourth of July to give speeches at the podium were President Miles of Select Council, Councilman A. J. McBridge, Agnew, Charles Kitchenman, J. W. Roth, and J. E. McLaughlin, Rev. J. P. Swindells of Kensington Methodist Episcopal Church (Old Brick), and Henry Bumm, who had inherited the property from Matthew Vandusen, the pioneer ship builder in the city.

“Amid hearty plaudits and to the tune of the “Star Spangled Banner” Charles A. B. Hetzel, the little son of Councilman Hetzel, of the Eighteenth War, unfurled the flag, and as it slowly floated in the breeze, there fell from it a huge shower of small flags, where were eagerly scrambled for by those in the audience….It was notable that in the large audience could be seen the faces of many of the old-time residents of Fishtown, and by their countenances they showed that they warmly welcomed the display of patriotism in their midst. Penn Treaty Park, when properly prepared, promises to be one of the most delightful public breathing spots in the city.”

In September 1893, as the Park was nearing completion and ready to be dedicated, Councilman Meehan, who had been instrumental in helping to create the park, presented to City Council a lithographic copy of Benjamin West’s painting of William Penn’s Treaty with the Indians. The descendants of Penn’s family had sent the lithograph to Meehan, but Meehan felt it really should belong to the city. The Penn family sent it to Meehan as a tribute for his services for helping to make Penn Treaty Park become a reality.

On October 8, 1893 excitement began to build, as the park was nearly ready to be dedicated. After long years of neglect and misuse, the famous Penn Treaty ground, a little over two acres, was going to be honored forever with a public square for all to enjoy.

Penn Treaty Park’s Opening Day – October 28, 1893

Opening Day

As the opening day of Penn Treaty Park approached, newspapers began reporting on the events that would mark the celebration. A veterans group, General D. B. Birney, Camp, No. 13, was expected to “turn out strong” for the opening of Penn Treaty Park on the 28th of October 1893. Another Philadelphia newspaper reported other activities that were in preparation:

The Red Men are making great preparations for the 211th Anniversary of the land of William Penn in Philadelphia, which will be observed on Saturday, October 28. Eighteen tribes will participate. Exercises will begin at 3 P.M. After the orchestra plays “America,” William Rowen, president of the Bramble Club, will deliver an address, to be followed by the “Star Spangled Banner,” quartet; oration by a member of the I.O.R.M.; benediction. Evening, line will form north and south on Shackamaxon street and Frankford road; move at 7:30. Chief Marshall, William Rowen; Cavalcade Marshal, Thomas Swan; committee of Bramble Club, William F. Stewart, chairman; Bramble Club, Vice-President Isaac Goodwin in command; tribes of I.O.R.M. in costume; delegations of Knights of the Golden Eagle; American Mechanics; Knights of Pythias; civic bodies.

The route will be Girard avenue to Fifth, to Norris, to Frankford road, to Girard avenue, to Otis, to Richmond, to Hanover, to Penn Treaty Park, where a grand display of fireworks will take place.

The afternoon program will be carried out at Penn Treaty Park, foot of Hanover street. The committee of the Bramble Club are: Representative William F. Stewart, Councilman William Rowen, Isaac Goodwin, Adam Belzer, Charles Fortner, William R. Weoters, William Carr, Joseph Rochelle, Dallas Smith, James coulter, Fred Shuman, R. F. Biddell, William Zehner, Charles Foster, Charles Siner, and W. H. Brady.

Penn Treating with the Indians as Re-Enacted 28 Oct 1893

Finally, all the various organizations were in readiness, and on the 211th Anniversary of Penn’s sail up the Delaware River, Penn Treaty Park had its official opening with a grand celebration. Papers across the country reported on the event, with estimates of 10,000 to 15,000 people in attendance. The Bramble Club, headed by Kensington councilman William Rowan, performed a re-enactment of the arrival of William Penn. Newspapers reported on the tremendous crowd that clamored to see all the various events including a huge parade the likes of which Philadelphia had not seen in years:

Every foot of ground in the Park was occupied by men, women and children. The house-tops in the vicinity were black with people, and the decks of boats in the river, the wharves, and, in fact every point of vantage were filled with spectators. The important events of October 28, 1682, were re-enacted in the presence of the great multitude.

A boat representing the good ship Welcome, speeded by wind and tide, sailed rapidly up the Delaware and anchored opposite the park. A small boat put off for the shore and, soon William Penn, wearing a broad-brimmed hat, knee breeches, and buckles and a wide blue sash, stepped upon the shore. As he landed, accompanied by sailors, and his associates, all the steam craft near by in the harbor blew their whistles. A red-coated British officer, an interpreter, and a number of residents attired in brown clothes, broad white collars, and old-time tower hats met the newcomers at the wharf and escorted them to the site of the historic elm tree.

About the wigwams near by were the old white-haired Chief Tamonend or Tammany and many members of the Delaware and Susquehanna tribes. The Indians were attired in picturesque garb, and with their blankets and warm moccasins were undoubtedly more comfortably clothed than were the scantly-attired aborigines who met the famous Quaker two hundred and eleven years ago. Over blazing fagots the treaty was conducted, the chief and his braves being seated on the ground, and receiving from the interpreter the assurances of peace and amity proposed by Penn.

After the pipe of peace was smoked, Penn and his associates returned to the Welcome, while the red men went into ecstasy over their presents.

Squads from nine Grand Army posts fired salutes with cannons and muskets, and thus ended the spectacular part of the program.

A stage for speakers had been erected on the north side of the park, and still father to the north were raised seats accommodating many hundreds of people. A platform on the east side of the stage was filled with several hundred school children, while all about these temporary structures surged the great mass of people who stood up for two hours while the exercises were being conducted. Councilman William Rowan, president of the Bramble Club, an organization of business men formed to promote the interests of the Eighteenth Ward, presided.

It was largely through the efforts of Councilman Rowen that the ground now used for the park was purchased by the city. Mr. Rowen made a speech which was loudly cheered. He said the grand old district of Kensington took this opportunity to show to Councils and the Mayor their appreciation of the acts which gave this breathing place to the northeast section of the city. “The Bramble Club,” he stated, will unite with other organizations to erect a monument in the Park to William Penn.”

Charles C. Conley, Great Chief of Records of the Great Council of the United States Improved Order of Red Men, delivered an oration. He said the future of our country rested with the girl, and the children on the platform applauded. The boys, he said, are to be the policemen of the country, by which, he added, he meant to pay a high compliment, for a guardian of the peace, whether he be president or patrolman, occupies an honorable position. He reviewed the circumstances of the treaty, and, concluding, said: “If we will ever recollect that in unity there is strength; if we follow the example of William Penn and his friend Tammany, who practiced that divine maxim while on earth of “Glory to God in the highest, on earth peace and good will among men,” then will we ever be the chosen of God, and the happiest people on His footstool., and under our starry flag a free republic forever.”

Other addresses were made by Thomas K. Donnally, Great Chief of Records of Pennsylvania, and David Conn, Great Sachem of Pennsylvania of the Order of Red Men. The singing was by school children, directed by Sarah A. Gilbert, supervising principal of the Adaire Grammar School, and James Simmington. The invocation and benediction were pronounced by Rev. William Swindells.

In the evening Kensington was brilliantly illuminated. Stores and residences were gay with flags, buntings, and lanterns. In the parade were the Bramble Club, with a float representing Penn and his attendants. The second division was made up of Red Men. The military division followed, with Grand Army Veterans, Knights of the Golden Eagle, Junior Order of U. S. Mechanics and Nights of Pythias. Volunteer firemen, New Year clubs and citizens in carriages brought up the rear. The procession was reviewed at Richmond and Hanover streets.

The parade was more attractive than any which has been given in the city for some time. The floats of the Red Men were magnificent, especially those presented by Narragansett Tribe, No. 43, representing scenes in the life of Captain John Smith which culminated in his marriage with Pocahontas. The chiefs on the floats were attired in white with white feathers. The scenes with the wigwams and camp fires were very interesting and real.

The procession was an hour in passing a given point. The New Year clubs, in their fantastic costumes, added much to the display and so many appearing in succession a little idea was given of what the effect would be if all the clubs united in one procession on January 1.

A grand display of fireworks in the park ended the demonstration.

And so Penn Treaty Park was officially opened. From that day, October 28, 1893, to the present, there has never been another such demonstration to match it!

Penn Treaty Park – 1893 – 2007

Penn Treaty Park

Beach Street Houses

In 1893, when Penn Treaty Park first opened, Mr. Henry Conan Merritt (1844-1917) was selected to be its first park superintendent. Merritt lived at 441 Allen Street for just about all of his 73 years. He was the son of Thomas and Sarah Merritt, old residents of Kensington who had five children with Henry the middle child. His father was a wharf builder and Henry followed his father into that line of work. Once Penn Treaty Park opened in 1893 and with Henry getting up in years (he was just about 50 when the Park opened), he probably welcomed a less strenuous occupation. It is said that with “only a nightstick, he single-handedly patrolled the park and kept the peace.”

When the City of Philadelphia decided to expand Delaware Avenue, they bought up all the properties on Merritt’s block of Allen Street, except for his family’s house, which as fate had it, was spared. The family did however lose a small piece of the property to Delaware Avenue.

Henry C. Merritt died at his Allen Street home on February 8, 1917, at the age of 73. His obituary listed members of the following organizations as welcome to attend his funeral, which presumably means he was also a member of these groups: Mt. Moriah Lodge No. 155 of the Free and Associated Masons; the Kensington R.A.C. No. 253; Kensington Commandery, No. 54: Knight’s Templars; Masonic Veterans’ Association; Captain John Taylor Temple, No. 24: O. of U. A.; Stonemen’s Fellowship Club; Superintendents of City Parks. His body was to be interred at North Cedar Hills.

Fountain in Penn Treaty Park 1893

During the tenure of Henry C. Merritt, many enjoyed the park and the events held there, including free band concerts were held at the Park. Some old time Fishtowners remember having concerts in the park back in the early 1950’s. Organizations like the 18th Ward Republican Club, the Palmer Social Club, and the Bramble Club, provided free ice cream for the children.

One interesting event that took place during Merritt’s term as Penn Treaty Park Superintendent, happened about the year 1910. The Federal Government appropriated $250,000 to build a new Immigration Station in Philadelphia to replace the “ramshackle building” that was “overcrowded and insanitary.” The Secretary of the Department of Commerce and Labor selected a site next to Penn Treaty Park where an old shipyard had been but was now in ruins. (This was the Reaney Neafie & Co., later Neafie & Levy Shipyard, the place were PECO would later build their plant in 1920).

The residents of the neighborhood complained that an immigration station would be a blight to historic Penn Treaty Park. Shipping men pointed out the value the station would have to the port of Philadelphia and several public spirited citizens argued that the park would be a symbol of patriotism for the arriving immigrants who would soon become citizens.

Apparently from 1907 to 1911, the U.S. Department of Immigration used Penn Treaty’s Pier 57 as a drop off point for newly arrived immigrants processed at the Gloucester, NJ, facility. They thought building a new station in this area of town would not be met with opposition. They were wrong.

While the factions were contending, Philadelphia’s Mayor John Edger Reyburn declared that he would not grant a permit to the government to build the station. “We don’t want it anyhow”, he said, “An immigration station is an annoyance.” The mayor refused to help find a better site in an acceptable location. A quarter of a million dollars was lost to Philadelphia when the station was built on the Jersey side of the river. It would not be the last time that Kensingtonians would reject plans to build near “their” Penn Treaty Park.

On a side note, during this time Lady Eileen Knox, daughter of Lord Ranfurly, and a descendent of William Penn is supposed to have once visited the Penn Treaty Park memorial. Lady Knox helped to carry the train of Queen Mary during the coronation of King George & Queen Mary in 1911.

The Beginnings of Decline

When Penn Treaty Park was first established it was under the jurisdiction of the Bureau of City Property. From recorded accounts, it would appear the Bureau did little in the way of caring for the park and the job fell to local residents who came together to help keep the park clean and enjoyable. When the Park was created there were still homes on Beach Street, but after Delaware Avenue was built and later expanded, many of these homes were demolished or gave way to factories and other commercial ventures. The Park became detached from the neighborhood. Reports show that after only twenty years of existance, the park was already showing signs of falling into disrepair and was described by one as a “dirty hole,” a place were “several parents forbade their kids to go.” The Park’s downward trend coincides with the death of its first superintendent, Henry C. Merritt in 1917.

Large Electric PECO Sign

The city did not appear to do much for the upkeep of the park. Adequate lighting was not installed until 1920, after Philadelphia Electric Company’s building was erected on the old Neafie & Levy Shipyard property to the north of the Park. A huge sign from the PECO plant illuminated the park and discouraged the young couples who were making a “lover’s lane” out of the place.

Thinking that the Park had no caretakers, PECO even tried to have the Penn Treaty Pier demolished so that the coal barges delivering to their plant would have an easiert. However, the local residents’ spirit was still alive and the attempt was rejected. The pier was refurbished in 1920 and later used for Harbor Police and Fire Units.

Recreation Wharf

While the Park was in some respects heading into decline, it was still being touted as a place to visit. Various publications promoting the Sesquicentennial mentioned it as a place that would be sure to get its fair share of tourists during the event. The American Legionnaires’ 8th Annual National Convention met in Philadelphia Oct 11-15, 1926 and in an article published in The Oxford Junction (Oxford, Iowa) the Penn Treaty Monument was listed as a place of interest to visit.

Starting in the 1920’s, Penn Treaty Pier (Pier 57) became the home of a unit of the Harbor Police, as well as a fireboat unit. The Merchant Marines also had a training ship, the “Annapolis” that docked at Pier 57. On June 7, 1931, the Park made the news when this unit of the harbor police had a boat explode at the foot of Columbia Avenue. The Superintendent of Police, William B. Mills, as well as six harbor policemen were hurt. The boat, named for the Superintendent, was on a trial trip and exploded as it pulled into Penn Treaty Park. After a little more then two decades, the Harbor Police and Fire Units were relocated.

Penn Treaty Park Map circa 1920

In the immediate years following World War II, local Fishtown residents once more turned their attention to cleaning up and restoring Penn Treaty Park. Led by the 18th Ward Community Council, a forerunner to the Fishtown Civic Association, which preceded the Fishtown Neighbors Association, the activists felt the only way the Park would get the attention it deserved would be to have the Park transferred to the Fairmount Park Commission. The issue was introduced to City Council, but Council transferred the Park from the Bureau of City Property to the Bureau of Recreation. Fearful that the Park would be relegated to a playground and lose its historical significance, State Representative Miles Lederer introduced a Bill in Harrisburg to make Penn Treaty Park a State Historic Site. Lederer’s Bill took several re-introductions before being approved.

Penn Treaty Park was of interest across the county as witnessed by the following report in a North Dakota newspaper that also ran in papers in Oakland, CA, St. Joseph, MO, and Lowell, MA:

“A Pennsylvania lawmaker says the misuse that has befallen the William Penn Treaty monument in Philadelphia shouldn’t happen to an historic shrine. State Representative Miles W. Lederer, Philadelphia Democrat, told the legislature Monday. “The monument (marking the spot where Penn signed a treaty with the Indians in 1682) has become dilapidated and is rapidly falling into decay. The Penn Treaty Park on which the monument is situated has become extremely rundown, the grass completely trampled out, the drinking fountain has disappeared, the restrooms are boarded up, the benches have disappeared, the automobiles park and drive all over the park and the iron fence used to protect children from falling into the Delaware river is in a broken condition. Lederer asked that Philadelphia be given $50,000 to restore the park.”

-The Bismarck Tribune, Bismarck, ND, Tuesday, March 15, 1949.

While Lederer may have come to a dead end at times, he kept up the fight. The 18th Ward Community Council petitioned the Fairmount Park Commission to assume control of the Park. State Rep Lederer solicited the help of Park Commission member John B. Kelly, Jr., to lend his support. Kelly was helpful in getting the Park Commission to agree to take over Penn Treaty Park, but the Commission was on a tight budget, that at that time was regulated by the State Legislature. Additional support was required to take over Penn Treaty Park. State Rep Lederer went to work in Harrisburg and with the help of others was able to secure a $75,000 allotment to be placed in the Fairmount Park Commission budget for the permanent care of Penn Treaty Park.

During this time, while Miles Lederer was calling for the restoration of Penn Treaty Park, one of the local papers started to pick up on the story. Paul Jones who wrote a column called Candid Shots mentioned visiting the park in its dilapidated condition:

“A low concrete marker, with metal tablet, is set into the ground under a youthful elm tree, planted by the Boy Scouts in 1932. This was to replace the great elm tree, blown over by the wind in 1810….An old settler was sitting on a bench, looking out over the river and smoking his pipe…[we] joined him. “This place is a disgrace,” he told us, “and nobody will do anything about it. Miles Lederer, at Harrisburg, and Phinnie Green in City Council, they both tried. But it didn’t do any good. Lederer’s got a couple of bills before the Legislature right now. Bet you 10 to 1 nothing’s ever done about it…You ever been in Washington Square? You know how nice it looks? Well, that’s the way Penn Treaty was, forty, fifty years ago. A fountain, flowers, calla lilies, tulips, walks all neat, not busted down the way they are now, plenty of benches, and people that behave themselves. There was a man here the carried a big bullwhip. Any kid that got out of line got a touch of the whip. If that didn’t stop him, the cops would arrest him….They boarded up that comfort station nine, ten years ago,” he went on pointing with his pipe stem. “Said they were going to fix it. Haven’t done a tap on it since.”

The old-timer went on to say, “the City owned the park, first it was the Bureau of City Properties, they didn’t do much repair, and proceeded to turn it over to the Bureau of Recreation, in about 1948. Now the Fairmount Park Commission was to take it over. In typical bureaucrat fashion, some folks from the city came out with all sorts of plans on what was to be restored, had a photo op, and then went away never to be seen or heard from again.”

The writer finished his column by stating that it was a good thing that Penn Treaty Park was hard to find, otherwise he wasn’t sure what tourists would think of us!

In 1954, jurisdiction of Penn Treaty Park was finally transferred from the Bureau of Recreation to the Fairmount Park Commission. The hard work of the 18th Ward Community Council and State Rep. Miles Lederer paid off. Soon public restrooms and a drinking fountain were refurbished. An officer of the Fairmount Park Police was stationed to patrol the park.

During the 1960’s and early 1970’s, as America’s economy began to change, a number of businesses and industries began to vacate the riverfront, and juvenile delinquents of the neighborhood started to make their way back into the park. The patrolman’s watch lasted until the early 1970’s and the park again started to fall back into decline. The vacating of the riverfront created more isolation in that part of the neighborhood, and Interstate I-95 bulldozed its way through the neighborhood in the 1960’s, literally cutting off the park from Fishtown, except for a few blocks of houses along Allen Street and parts of Richmond Street. The park again became a “lover’s lane” with youths drinking alcohol and generally trashing the place.

Bicentennial & Tercentenary Celebrations, the Expansion of the Park

The community’s attachment to the Park would not die. As the Bicentennial of America approached, the Kensington Community Council and the Fishtown Civic Association worked on having the Park renovated. The Kensington Community Council dated back to the year 1939. A long time member of the group was Henry C. Kreiss (1910-1990) who joined the Council in 1941. Mr. Kreiss was nicknamed “Mr. Kensington,” due to his love of the community and his active participation in its promotion and upkeep. Kreiss was very instrumental in helping to preserve Penn Treaty Park, acting as one of the main advocates to have the Fairmount Park Commission take it over.

Another supporter of the Park and a colleague of Kreiss’ in his efforts to renovate and promote Penn Treaty Park was Dr. Etta May Pettyjohn (1909-2005). Pettyjohn was the daughter of Theodore T. Pettyjohn, a long time local tugboat captain, and Alma B. Pepper. Pettyjohn’s parents, originally from Delaware, moved to Philadelphia and lived for a time in several different homes on the 800 block of East Thompson Street, where Dr. Pettyjohn was born. She graduated from Kensington High School for Girls in 1925 and three decades later, (after getting her bachelor’s, master’s, and doctorate degrees all from the University of Pennsylvania,) returned to Kensington High School as its principal (1956-1971). After her retirement, along with the Kensington Community Council and the Fishtown Civic Association, she was the driving force behind the restoration of Penn Treaty Park.

In June 1970, Dr. Pettyjohn gave a talk to the Kensington Community Council titled, “The History of the Park with Recommendations for Its Use and Rehabilitation for the Bicentennial.” In her address Pettyjohn allowed the community to dream of a day when Penn Treaty Park would have its own interpretive museum:

Proposal: The Expansion and Development of Penn Treaty Park, Kensington, Philadelphia, PA.

(For the Opening of Space for Recreation, and for Community service, as a Memorial to William Penn, his Treaty of Friendship with the Indians, and the Implementation of his Concept of Social Justice.)

This proposal requires the extension of the present Penn Treaty Park grounds in a westerly direction along the bank of the Delaware River (toward the Benjamin Franklin Bridge), to implement the following plan:

The area, cleared of present buildings, should be developed with the reconstruction of Fairman’s Mansion or some comparable building, a large parking lot to accommodate buses and cars, and benches along the river front for public recreation.

The mansion should house a museum where artifacts or reproductions pertaining to William Penn’s dealings with the Indians could be displayed. These realia might include personal possessions of William Penn, memorabilia made from the treaty elm which fell during a storm on March 3, 1810; originals or copies of paintings commemorating the treaty spot, and Indian relics of every description.

The temperature-controlled building should house a lecture room capable of seating 150 to 200 people. Here, with musical background and narrated slides, the account of Penn’s meeting with Indians at Shackamaxon could be presented to groups of students, tourists, and other visitors to the park.

Lavatory facilities for men and women as well as drinking water should be provided.

The plans should include living quarters for a full-time caretaker and a shop where prints, color slides, reproductions of Indian and Penn artifacts and related brochures and books could be sold to assist with the financial upkeep of the buildings.

Because of its isolated location on the river front, it is possible that consideration should be given to walling the entire compound for security purposes.

The Philadelphia Electric Company’s transformers should be removed from their present position in front of the park.

Directional signs to the park should be posted at advantageous locations on nearby streets and highways, including the new and nearby Delaware Expressway #95.

Dr. Pettyjohn’s dreams for Penn Treaty Park seem to fit in with precisely the type of development now being sought for Philadelphia’s waterfront. The era of the build up to the Bicentennial Celebration would have been an ideal time to share Penn’s Treaty with the rest of the world.

While Pettyjohn’s museum was never built, there were some extensive renovations to the Park. In the preparation for the Bicentennial, the old Pier 57, in disrepair and no longer used except for fishing, or for diving into the river, was finally removed. The original Penn Society Memorial Obelisk was moved from the northwest corner of the park, closer to the original sight of the Treaty Elm.

This Bicentennial renovation renewed the fighting spirit going in Fishtown. Again, the Fishtown Civic Association and the Kensington Community Council, as well as other concerned citizens, led the charge not only to further restore the Park, but now also to expand it. With several tracts of vacant property to the south of the Park, efforts were made to acquire the land and expand the park from Columbia Avenue south to Marlborough Street. The “Warner Tract” of about 4 _ acres, and the “Penn Atlantic Millwork Tract” of 1 acre, were both secured. All that was needed was to remove a large warehouse on the properties. After demolition of the warehouse and landscaping of the new 5 _ acres of expansion, the area was incorporated into Penn Treaty Park by an ordinance in 1982. A fishing pier was also erected in the newly expanded park plan.

1982 was a special year because it marked the Philadelphia’s Tercentenary Celebration. In conjunction with the yearlong event, various activities took place at Penn Treaty Park. The Daughters of the American Colonists commissioned Frank C. Gaylord, the sculptor who would later do the Korean War Memorial in Washington, DC, to carve a statue of William Penn. The statue of Penn was dedicated in Park ceremonies in 1982 at the Tercentenary.

Another Tercentenary celebration that took place at the Park in 1982 was a William Penn Sabbath that was held on October 24, 1982, by the Lower Kensington Ecumenical Council and the members of the Fishtown Civic Association. After a processional rendition of the Battle Hymn of the Republic and the singing of the National Anthem, John Connors of the Fishtown Civic Association voiced the welcome and opening remarks. The Rev. Edward Cahill of Immaculate Conception R.C. Church gave the invocation for the day. There was silent prayer and words of assurance by Rev. Reinhard Kruse of Summerfield U.M. Church. Betty Quintavalle of the Lower Kensington Ecumenical Committee read the scripture along with James Winn of the Fishtown Civic. First Presbyterian Church of Kensington minister, the Rev. Charles R. Schafer, held vesper prayer and Kensington United Presbyterian Parish minister Rev. E. Bradford David gave an address on William Penn – Man of Love.

Henry C. Kreiss – “Mr. Kensington” – read William Penn’s Prayer for Philadelphia, which was followed by benediction given by the Rev. Robert Larson of Pilgrim Congregational. The program ended with America the Beautiful as the recessional.

The United American Indians of the Delaware Valley hosted a three-day Pow-wow at the climax of a weeklong encampment in what is now the new section of Penn Treaty Park. Eastern Native American architecture and construction methods were demonstrated with the erection of a longhouse and two wigwams. The longhouse was the scene of traditional Indian worship services during the week and offered visitors a rare glance at the life-style that William Penn may have encountered. On Sunday, October 31, 1982, the American Indians, in full regalia, joined costumed Fishtowners for a re-enactment of Penn’s Treaty of Friendship, complete with an authentic replica of the Wampum Belt.